An Adult Adoptee Reflects On Adoption During National Adoption Month

If everything that made you who you are were stripped away, who would you be?

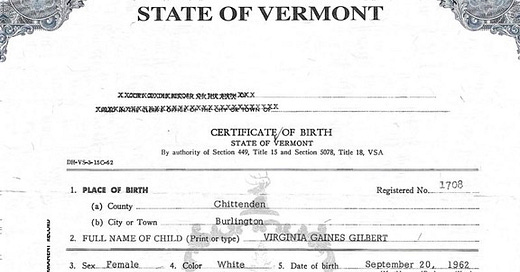

My amended birth certificate that arrived nine months after my birth

November is National Adoption Month, when people are encouraged to learn about adoption, recognize people who have been impacted by adoption, and organize adoption-related events, whatever that means.

Created in 1995 by President Clinton, National Adoption Month didn’t exist when I was a child. I wonder: if it had, would I have felt differently about coming into my family in a non-traditional way? I don’t ever remember a time when I wasn’t preoccupied with trying to figure out where and how I belonged, or whether adoption was really a good thing since my mother choked up so often when she spoke of it.

I did beg to hear the story of how I was born, which my parents told me at bedtime. That story began not at birth, but at six days old, when my original birth certificate was sealed, and I was given a new name, a new family, and a sanitized narrative of adoption: my first mother loved me so much that she gave me to different parents to raise.

My adoptive parents, Mag and Dick, turned these events into a bedtime tale that shaped how I perceived and walked through the world. I felt as though I were encased in an invisible film. And I had to strain, through this barrier, to feel connected to anyone. I recall one spring day when I was six or seven, my toes gripping the dewy grass on our front lawn, my eyes traveling from one family member to another, telling myself, “that is my mother, that is my father, that is my sister.” It was as if I were trying to grasp how E equals mc squared.

This popular but frankly sinister adoption trope — that a mother gives away her child out of love — was one that adoption brokers urged my parents to tell me because that was the party line. My parents were kind people and I have never doubted that they meant well by trying to ensure that I didn’t feel rejected.

But what I felt was terrified and confused, because that story made no sense. It made me feel exactly the way adoption writer Anne Heffron describes her experience growing up:

“Something is wrong. No one understands.”

Here’s the truth about adoption: it does not start when a child is adopted. It begins with the severance of a mother-child bond, and with that, an adoptee’s genetic and cultural legacy. If the person who’s supposed to love you more than anyone in the world hands you over to strangers, that means that anyone who loves you could up and decide, “I loved you yesterday, but you know what? Today I’m done with you.” Once this realization spreads its tentacles through your psyche, you begin to feel that all love is tenuous at best, dangerous at worst.

If you were brought up by your biological parents like most people, you take many things for granted. The cherished lemon squares that were handed down through generations, the preponderance of wavy-haired, freckled relatives, the scholars, the deep thinkers, the flute players — all of these inherited traits and affinities give you context. They root you.

Now imagine: every single thing that makes you who are is stripped away, until you are left attached to nothing, like a solitary fabric square that got loose from a quilt. If this were your reality, who would you be?

I was sure I would solve my existential conundrum by birthing my own children. But as I sat in a wicker rocking chair 25 years ago cradling my days-old son, I felt untethered, almost dizzy. The objects in the nursery I had so painstakingly decorated — the gingham window treatments, the cherub-patterned crib bedding, the distressed white bookshelf lined with childhood classics — looked as if they’d been curated by a mother who knew exactly who she was. Clearly, I did not.

I stared down at this precious, gurgling bundle who depended on me for everything, trying not to crumble under the weight of questions that had no answers. Why did I think that growing up in a Pottery Barn Kids catalog would ensure my child would lead a charmed life? Why had I agreed to raise Jewish children when I was raised Christian — by a minister and the daughter of missionaries, no less? Why had I never felt connected to Christianity, anyway?

How was I going to pass on an identity to my son when I didn’t even have one?

I was in therapy on and off from 8th grade through college and no therapist, ever, suggested that being adopted might have contributed to the attachment trauma playbook I’d been following since early childhood: quicksand-like bouts of depression, crippling anxiety, tortured relationships, and difficulty focusing. What I felt, more than anything, was the psychic homesickness that comes from a lack of genetic mirroring: seeing your DNA reflected in the people around you.

I want to make clear that my parents loved me. In fact, my mother loved me to the point of obsession, but that’s fodder for another post. I had a good childhood in many ways. I got a top-notch education. We traveled through Europe, lived in the mountains of Mexico for a year. We went to museums, the theater, the tea room at Lord & Taylor. The four of us sat in front of a crackling fire in the living room, acting out the parts from My Fair Lady. When I showed promise of being a good writer, my parents and sister could not have been more enthusiastic cheerleaders.

And yet.

Mom and Dad hailed from an era when “good families” didn’t acknowledge their problems. Dad’s parents divorced — scandalous for the South in the 20s — and he rarely saw his father. He saved enough men as a teen in WWII that he was awarded a Purple Heart. He came home from the war only to lose his beloved sister to suicide, a fact that got repackaged as “she died accidentally when she was cleaning the hunting rifle.” Mom never lived anywhere more than a year during the Depression because her family moved wherever her father could find work. She was just 15 when he died a gruesome death from bone cancer, and her older siblings had to drop out of college to help support their mother. So I understand why my parents didn’t have a lot of tolerance for what they perceived to be my lack of gratitude for a life that, on the surface, was relatively trouble-free.

If Mom and Dad had gotten any substantive adoption education, which simply wasn’t available back in the 60s and 70s, they might have understood that expecting gratitude from a child who has been divested of their entire heritage without their permission is not realistic. If we had had a real therapy session when I checked myself into the psych ward at Georgetown University Hospital during my senior year of college in a clumsy, frantic attempt to get my family to understand I CAN’T BE WHAT YOU WANT ME TO BE!!, then maybe we could have finally said the things that needed to be said. Maybe our family could have healed. But instead my mother sobbed that no one appreciated her, my father and sister sat in deafening silence, I fumed behind crossed arms, and the wide-eyed psychologist said nothing until the end of 50 minutes when he announced with palpable relief that we were out of time.

No one knew then that my issues were the norm among adoptees, not the exception. Studies show that adopted people are twice as likely as non-adopted folks to suffer from mood disorders and behavioral issues. Worse, we are 4x more likely to commit suicide than those raised by their biological parents. We are, as a group, not known for being a happy-go-lucky bunch.

I checked out of the psych ward shortly after one of my comrades smashed his head through an aquarium during his family therapy session, sending gallons of water and dozens of iridescent fish cascading down the hall.

My parents, sister, and I never spoke about my time in the hospital again. We remained a family, but we were never the same. My mother felt wounded, my father had absolutely no idea what to do with me, and my sister tried to cheer everyone up. I resolved to work harder to spackle over the woes that plagued me so others would be more comfortable.

Having had two divorces, I can attest that twisting oneself into a pretzel is not a good life strategy. The thing that saved me, besides three years of committing to rigorous honesty in Alanon, was embarking on a career where I get to talk to people about the things that go unsaid. After 20 years of having these conversations, I can assure you that that which remains unsaid starts screaming from the rooftop as years pass, and generations proliferate.

A few months ago, I fell in love with a memoir called Ancestor Trouble. Written by Maud Newton, it’s an epic exploration into the way her family history — both the good and the terrible — insinuated itself into the present. The writer describes how she used the genetic technology 23andMe, as well as investigative reporting into her ancestry, to piece together a narrative that explained why she is the way she is, and what she needed to do to exorcise what was toxic in her inheritance. In her case, that meant healing through ancestral medicine rituals and taking action towards restorative justice for her father’s racism and ancestors who owned slaves.

I’ve been in reunion with my birthmother Diane since I was 20. It’s been a complicated relationship — how could it not be, when a mother and daughter don’t know each other for 20 years? — but at some point during the reading of Ancestor Trouble, I felt an urge — like a freight train barreling inside me — to transcend the decades of hurt feelings on both sides.

During our recent phone conversations, she and I have gotten to know each other not as a mother and a relinquished child, but as two women who had been traumatized by society’s dictate that unwed mothers didn’t deserve to raise their own children. We both understand each other’s perspectives in ways we didn’t before. I am so grateful that she is still on this earth, and that I have the opportunity to explore, and heal, the patterns in her family that have shown up in my own life.

I wish my mother Mag were still alive so we could work things through too. She was traumatized by seven miscarriages after having my sister, but she never talked about it. She was a devoted product of her era, though, so she probably wouldn’t have been comfortable having the honest conversations I longed for.

But now for some happy news! Beginning this January, I will be taking Maud Newton’s class, Writing About Ancestor Trouble, which “focuses on acknowledging troubled family histories honestly, open-heartedly, and with imagination.” I don’t know if I’ll ever publish a memoir. But I do know it’s high time to say things that need to be said, and blend two lineages into one integrated life.

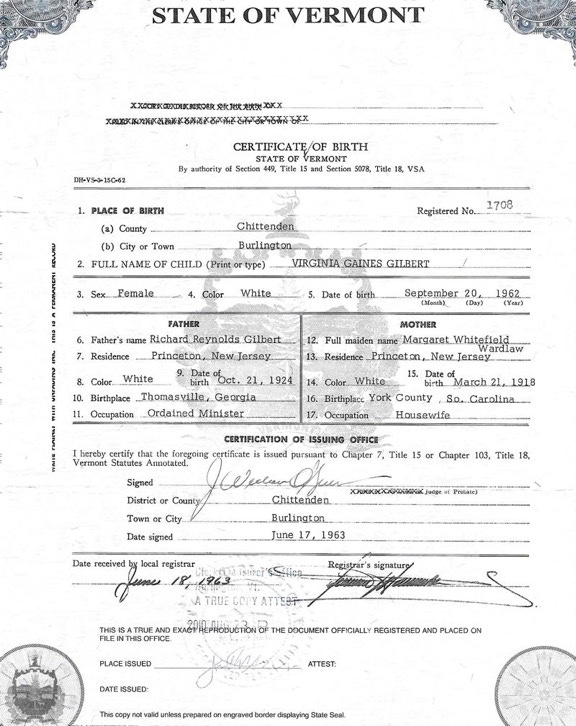

My original birth certificate. For the first six days of my life, I was Lara Ann, named after Julie Christie’s character in Dr. Zhivago.

It’s National Adoption Month. Go listen to an adoptee.

A suggested title for your memoir "Things that go unsaid" or "Things Unsaid".